- Home

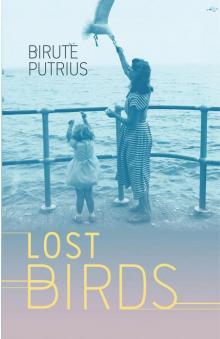

- Putrius, Birute

Lost Birds

Lost Birds Read online

Lost Birds

© Copyright 2015 by Birute Putrius Birchwood Press. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopying or recording, except for the inclusion in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction.

Names, characters, places, and incidents either are a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Published in the USA by:

Birchwood Press

Send inquiries to [email protected]

www.birchwoodpress.com

ISBN 978-0-9965153-0-6 (paperback)

978-0-9965153-1-3 (ebook)

Book interior layout by Darlene Swanson • www.van-garde.com

For Max and Anna and Algis

Becoming American

Irene Matas, 1950

It took eleven long days and nights to cross the Atlantic Ocean on the General Howze, a GI troop transport. For five days it stormed, raising mountains of water that made me feel so small. Everyone was sick, including my mother. My older brother, Petras, couldn’t get out of bed for two days, which made my mother frantic since the men and women were separated on different levels. My father took care of Petras as best he could until the sea finally calmed. The next day, my mother stood with me and my brother on the deck, holding our hands as she pointed to the schools of flying fish leaping out of the blue water. “Fish can fly!” I said, delighted, not knowing it was possible. When I turned to look at my pale brother, I saw he was smiling, his eyes shining as he stared at the magical creatures that were part bird and part fish.

On the last day of our voyage, our family stood on deck watching the great city of New York in the distance, with its towers touching the sky. It was so amazingly different from our displaced-persons camp in Bavaria, where I was born after the war. When we reached New York Harbor, we disembarked like birds thrown out of our nest, staring at the immense forest of skyscrapers. I was a timid girl, and the huge city scared me. Everything seemed too big.

“So this is America?” my mother asked my father.

“Well, it isn’t Kaunas,” he answered, his face exhausted by the journey. The sharp October wind blew newspapers and dust across the grimy street, clearly distressing my mother, who craned her neck to see the tops of the buildings.

“Oh, Viktoras, it’s so big, and there’s no grass. Where will the children play?”

My weary father put a reassuring hand on her shoulder. “Don’t worry, Dora, Mr. Jankus said there was a part of Chicago as green as Samogitia.”

That same day we boarded the train to Chicago.

Our American sponsor, Mr. Jankus, met us at the train station and shook my father’s hand heartily. “Welcome to Chicago,” he boomed in American-accented Lithuanian, a cigar hanging loosely from his protruding lower lip, sending smelly puffs into the city’s gloom. “I’m George Jankus, and this is my wife, Adele.”

“Viktoras Matulaitis,” my father said, introducing himself and his family.

“I’d change that name to Victor Matas if you want to get work here,” said Mr. Jankus.

“Is that so?” asked my father, shooting my mother a worried look.

“My last name used to be Jankauskas, but no one in America could pronounce it.”

I stood below the thicket of grownups, my skinny blond braids freshly redone with large plaid bows, noticing how our sponsor’s belly strained the buttons of his brown pinstriped suit.

His wife, Adele, a tight-lipped woman wearing a hat like a plate of flowers, blinked nervously as she escorted us to their blue Studebaker. My parents, Petras, and I stood there in our wilted, refugee-camp clothes donated by St. George’s Church. The Lithuanian-American parish had sent boxes of used clothes to the displaced-persons camps in Germany after the war. Its members had agreed to sponsor Lithuanian families wishing to immigrate to Chicago, promising to help them find shelter and work.

Mr. Jankus escorted us to his Studebaker, where our cardboard suitcases were swallowed up in the trunk. My parents and brother squeezed into the back seat of the car while I sat on my father’s lap. Mr. Jankus drove us to the South Side, pointing out the various factories where my father might find a job. “There’s more work in Chicago than pigs in the stockyards,” he said, grinning, the foul cigar bobbing up and down as he spoke. We stared out the window at the industrial neighborhoods filled with factories and brick two-flats, searching for the green part of Chicago that looked like Samogitia. The South Side was one poor neighborhood after another, filled with Negroes, Gypsies, and runaways from Eastern Europe.

Clutching my father’s hand, I stepped out of the Studebaker as Mr. Jankus walked to a decrepit storefront that was to be our new home. Once he unlocked the front door, we stepped inside a large room with shelves along three walls, which smelled of mold and stale tobacco. The only light came from the streaked and dusty storefront windows, while the rest was a dark cave with one light bulb hanging over a wooden table. Two beds and a dresser stood forlornly in the back of the store. A dust-covered treadle sewing machine sat abandoned in the corner, and an old stove hunched close to the sink, next to the minuscule bathroom.

Holding our suitcases, we stood there, disappointment shrouding us. No one said a word until Mr. Jankus tried to cheer us up by telling us that the church had finally found a used refrigerator.

“It’s coming tomorrow,” added his wife as she handed my mother a bucket with rags, soap, brushes, and a can. “Missus, these are some cleaning supplies,” she instructed, pulling out a can of glass wax.

“Call me Dora,” said my mother.

Mrs. Jankus looked up impatiently and cleared her throat. “Dora, this is for cleaning windows. You pour a bit of this on a rag and make circles until you cover the window. Then you let it dry and wipe it off with a clean rag. She demonstrated by smearing the cloudy pink liquid on a small section of the dirty window while my mother studied the perplexing ritual.

Afterward, Mrs. Jankus went to the car to get a bag of groceries and some old sheets. Her husband told my father how lucky we were to have Lithuanians help us. “When we came to Chicago in 1914, no one helped our folks. Hardly no food on the table and everyone worked the stockyards, even us kids. You read that book The Jungle by Mr. Upton Sinclair?”

My father shook his head. “As a high school teacher in Lithuania, I read a great deal, but never any books in English.”

Mr. Jankus shrugged. “I didn’t read it either, but they say it tells a sad story about the Lithuanians working at the stockyards, but it’s different now that the unions cleaned up the stockyards. Maybe I could fix you up with a job there?” He took off his brown fedora and scratched his short gray hair, the folds of his chin jiggling. “Nobody fixed us up with a job when we came here. Heck, we almost starved. We at St. George’s remember those days, so we weren’t going to let that happen to you DPs. At church, you’ll meet the Vitkus family, one of the other DP families our church sponsored. They live right down the street,” he said, pointing out the dirty front window.

Mr. Jankus shook his head. “It’s such a shame how the horrors of World War II just continue. Those damned Communists just swallowed all of Eastern Europe like it was theirs. Sons of bitches,” he mumbled under his breath.

My father thanked him and shook his hand.

“Mr. Matulaitis, you call if you need anything,” said Mr. Jankus, the cigar still clenched between his teeth. “This is a great country. You work hard, you can make it here. Ain’t that right,

Adele?” His wife looked at us sideways, as if she wasn’t so sure. She opened the door and turned back to us, her purse locked safely in the crook of her elbow. “Nice meeting you,” she said mechanically as she nodded to my mother, ushering her husband out and closing the door behind them.

My father seemed both grateful and burdened by this help.

“What’s a DP?” my brother wanted to know.

“Displaced person,” my father said, frowning as he looked around the dank and dismal store. “I want you to remember this,” he said, looking into our eyes with such seriousness. “We’re not immigrants like the Jankus family. They came to America long ago looking for work and a better life. We are exiles. Never forget that. We came to this country for shelter until the Soviets leave our country and it’s safe to return home. It won’t be long now. The Free World will never stand for an occupied Europe. They’ll make short work of Stalin, and then we’ll go back home to Kaunas.” He patted our heads and smiled. Ever the teacher, he added, “There are fewer than four million people in the world who speak our Baltic language, one of the oldest languages, the closest to ancient Sanskrit on the tree of languages. We must keep it alive until we return so that the Russians don’t wipe us from the face of the earth.”

Petras and I hadn’t known we were exiles. We knew we were Lithuanians, but now we were also DPs and exiles. This sounded serious, but we weren’t sure why. While examining the room, Petras mumbled his complaints under his breath, “This place doesn’t look any better than the camp we left behind in Germany. I thought America was rich.”

“I thought we were going to a home with flowers and apple trees.” I was looking around the scary and lonely store with nothing on the shelves to sell. If this was America, I hated it. “Mama, I want to go back home, to our camp,” I whined, on the verge of tears. “To the Danube to catch minnows in my bucket.” I had an aching longing for our refugee camp, a converted cavalry stable where we had lived in one small room.

“Irena,” my father interrupted, “don’t you remember how every time it rained, the smell of horse manure returned?”

For me it had been cozy having my family tucked in tightly around me. I held onto my mother’s skirt for comfort until I noticed a gaggle of children with their faces pressed to the front window, straining to see who had moved into the old store. There were two Negro boys and three young girls with dark eyes and long tangled hair and small gold earrings, smiling and waving their arms as if they wanted us to come out and play. Petras looked to my father for permission, but my mother hissed, “Gypsies,” and I could see by the look on her face that she didn’t like them. “They used to steal my father’s horses in Lithuania.”

“Dora, please! These are children, not horse thieves.” My father gently chased them away from the windows while my mother wondered what she could do to cover the windows. Newspaper would have been fine, but since we didn’t have any, she pulled out the tin can of glass wax and some old rags. “This will give us some privacy.” Petras and I were told to smear the pink liquid onto the windows while she went to open cans of soup for our supper. We had hardly finished a row of cloudy circles when one of the Gypsy girls returned and pressed her face against the glass, flattening her nose and sticking her tongue out. I laughed and also stuck out my tongue, and we made faces at one another. Soon they were all back at the window. I drew a funny face on the window with the glass wax and the Gypsy girl clapped. Soon Petras and I were dancing and making faces, laughing so hard that my mother came over to chase the children away so we could finish smearing the windows.

That night, I slept curled into my mother in one narrow bed while my father slept with my brother in the other bed. Our khaki GI-issue wool blankets from the camps were as scratchy as ever. The night seemed long, and I felt far away from the only home I had known. When I woke in the middle of the night, I could feel the bed shaking as mother cried into her pillow.

“Why are you crying, Mama?” I finally asked.

My mother wiped her tears on the blanket. “I’m worried about your grandparents in Kaunas,” she whispered. “I miss them so much.”

“Tell me again about your house in Kaunas,” I asked, knowing how she loved to describe it.

My mother didn’t say anything for a moment and then sighed deeply. “It had many rooms filled with light,” she whispered the familiar version in my ear. “With china teacups and silver candlesticks and flower boxes filled with red geraniums in every window.” It soothed us both to imagine those rooms. “When I left my home in Kaunas, I thought it was only until the war ended. But now an Iron Curtain has come down in Europe, sealing it off from the rest of the world, and there’s no going home.” She wiped her tears.

In the morning, when I opened my eyes, I thought I was back at the DP camp, and it took me a moment to realize it was the store in Chicago. And yet something had changed. The gray and dingy room was transformed by the rosy glow of the glass wax. The sun shining through the bubble-gum pink of the smeared windows bathed the room in a cheerful glow like a fairy-tale spell. The sheets on my bed shone, as did my mother’s sleeping face, no longer tired and worried. In this light, she looked younger. Everything in the grim storefront had been magically transformed.

When I woke my mother to show her, she squinted into the bright light, indifferent to everything. “Irena, go back to sleep,” she murmured, turning away from the window, leaving a mountain of a shoulder.

But I couldn’t go back to sleep. This was a magical hour. Waving my hands back and forth, I saw they were glowing. A man walked by outside, and I could follow his dark pink shadow across the large windows. I was enchanted.

Later that morning, while my parents were busy with cleaning the store, Petras and I ventured outside to see how America looked. My parents said we had to stay on our block. Old two-story brick apartment buildings lined the street, and at the corners, a few small stores like ours—one sold fruits and vegetables while another sold cigarettes and held racks of newspapers and magazines. We went to the end of the block and found one of the Negro boys who had peered into our window the day before. Soon the tangle-haired Gypsy girls appeared, and they were all speaking words I couldn’t understand.

“Are you American?” they kept repeating. I smiled and shrugged, not understanding a word. Pointing to myself, I said, “Irena, DP, exile,” but they all looked at me as if frogs were leaping from my mouth. The oldest girl pointed to herself and said, “Marlena,” while the younger ones introduced themselves as Delphina and Seraphina. The Negro boy’s name was Lovey. And just like that we were pulled down the block to play in a trash-littered lot they called a “prairie.” We swarmed an old fallen tree like busy ants. “This is our ship,” my brother said to me, pointing to the tree. “And here is your sword,” he yelled, handing me a long stick. “We’re sailing the seas through storms to fight off Russian pirates.” Holding his stick, he yelled, “Attack,” as we bravely fought the spindly branches.

Every day, we ran around the block with the Gypsies like feral children, faces smudged with dirt, climbing fences and playing tag in the cinder alleys until dusk. Being the youngest, I often tripped and fell, skinning my knees bloody on cinders, crying and screaming while my mother tried to pick them out with a pair of tweezers.

“Are we Americans, Mama?”

She glanced up at me. “No, we’re Lithuanians. And we’ll go back home as soon as our country is free again, God willing.” She picked out a few more cinders as I screamed, but then her nerves gave out and she dabbed iodine on and bandaged my knees, hoping for the best.

“Do you have to play with those rough children?”

“They’re my friends, Mama.”

By the end of the second week, my father had changed our last name to Matas. He counted himself lucky because a Lithuanian acquaintance got him work at the Nabisco factory in Marquette Park instead of the stockyards, and my mother got a job cleaning offices downtown

at the Prudential Building. In each place, there were other Lithuanians who would help them. Though my father could speak four languages fluently, he knew very little English, so teaching was out of the question. Few of his friends, who had been accountants, lawyers, or writers, could resume the kind of lives they had left behind. My father worked the day shift while my mother took the evening shift so that someone would always be home to care for us. Before long, Petras enrolled in the Precious Blood Catholic School, got his uniform, and left for school down the street. I started morning kindergarten, and in the afternoons I stayed with Mrs. Vitkus, who lived across the street from the church in a one-room attic. Her daughter Magda was older, but she still played with me. Her son Algirdas, whom the kids called Al, never wanted to play with me, but he followed my brother like a shadow. Now we had some Lithuanian friends and it was easier to speak to them.

It turned out that Lovey, who lived in the large brick apartment building next door, was in my kindergarten class. His brother, Charlie, walked to school with Petras, who now wanted to be called Pete. Instead of Irena, the nuns started calling me Irene, as did my friends.

Before I met Lovey, I had never seen a Negro before and so I kept examining him as if he had stepped out of a storybook. One day, when he came over to play and asked for the bathroom, I took him to the small one in the back of the store. I had never seen a penis before, and I was amazed, wondering what it was and why I didn’t have one. I bent over, curious to get a better look and was about to ask him why he peed standing up when my mother came in and shrieked, “Irena, what are you doing?”

I jumped, knowing from her tone of voice that I had done something wrong. “Nothing,” I answered. “Lovey had to use the bathroom.” But I could see from her expression that I was in big trouble, though I didn’t know why. After sending Lovey home, she spanked me and sent me to the corner. “Never do that again,” she said sternly. I stood in that corner feeling angry and confused, still unsure of what I had done wrong.

Lost Birds

Lost Birds